3D-printed designs and 3D-woven clothing by tech startup Unspun hints at what the fashion industry’s sustainable, zero-waste future could look like.

Over 50 years ago, the classic Levi’s® Trucker jacket was introduced. But we are not one to rest on past accomplishments.

Now, the brand is turning to futuristic modes of innovation in manufacturing, pioneering a new approach in denim design.

Fast Company joined Levi’s® Head of Global Product Innovation, Paul Dillinger, at the Autodesk Pier 9 Workshop in San Francisco to witness how Levi’s® has been experimenting with 3D printing, creating digital renderings of the denim jacket which is essentially a shell of what the “real” thing could look like.

Concordia researchers have developed a new 3D-printing technique that uses sound waves to directly print tiny structures onto soft polymers like silicone with far greater precision than before. The approach, called proximal sound printing, opens new possibilities for manufacturing microscale devices used in health care, environmental monitoring and advanced sensors. It is described in the journal Microsystems & Nanoengineering.

The technique relies on focused ultrasound to trigger chemical reactions that solidify liquid polymers exactly where printing is needed. Unlike conventional methods that rely on heat or light, sound-based 3D-printing works with key materials used in microfluidic devices, lab-on-a-chip systems and soft electronics that are hard to print at small scales.

This work builds on the research team’s earlier breakthrough in direct sound printing, which first showed that ultrasound could be used to cure polymers on demand. While that earlier method demonstrated the concept, it struggled with limited resolution and consistency. The new proximal approach places the sound source much closer to the printing surface, allowing far tighter control.

A new spin on robotics, thanks to a novel 3D printing method

3D bioprinting, in which living tissues are printed with cells mixed into soft hydrogels, or “bio-inks,” is widely used in the field of bioengineering for modeling or replacing the tissues in our bodies. The print quality and reproducibility of tissues, however, can face challenges. One of the most significant challenges is created simply by gravity—cells naturally sink to the bottom of the bioink-extruding printer syringe because the cells are heavier than the hydrogel around them.

“This cell settling, which becomes worse during the long print sessions required to print large tissues, leads to clogged nozzles, uneven cell distribution, and inconsistencies between printed tissues,” explains Ritu Raman, the Eugene Bell Career Development Professor of Tissue Engineering and assistant professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

“Existing solutions, such as manually stirring bioinks before loading them into the printer, or using passive mixers, cannot maintain uniformity once printing begins.”

Additive manufacturing (AM) methods, such as 3D printing, enable the realization of objects with different geometric properties, by adding materials layer-by-layer to physically replicate a digital model. These methods are now widely used to rapidly create product prototypes, as well as components for vehicles, consumer goods and medical technologies.

A particularly effective AM technique, called direct ink writing (DIW), entails the 3D printing of objects at room temperature using inks with various formulations. Most of these inks are based on fossil-derived polymers, materials that are neither recyclable nor biodegradable. Recently introduced lignin-derived inks could be a more sustainable alternative. However, they typically need to be treated at high heat or undergo permanent chemical bonding processes to reliably support 3D printing. This prevents them from being re-utilized after objects are printed, limiting their sustainability.

What happens to soft matter when gravity disappears? To answer this, UvA physicists launched a fluid dynamics experiment on a sounding rocket. The suborbital rocket reached an altitude of 267 km before falling back to Earth, providing six minutes of weightlessness.

In these six minutes, the researchers 3D-printed large droplets of a soft material similar to the inks used for bioprinting —a developing technology that shows huge potential for regenerative and personalized medicine, tissue engineering and cosmetics. Bioprinting involves 3D-printing a mix of cells and bio-inks or bio-materials in a desired shape, often to construct living tissues.

The experiment was called COLORS (COmplex fluids in LOw gravity: directly observing Residual Stresses). Using a special optical set-up, the researchers could see where the printed material experienced internal stresses (forces) as the droplets spread and merged. Stressed regions stand out as bright colors in the experiment. Investigating how and where these stresses emerge is important because they can get frozen in a material as it solidifies, creating weak points where 3D-printed objects are most likely to break.

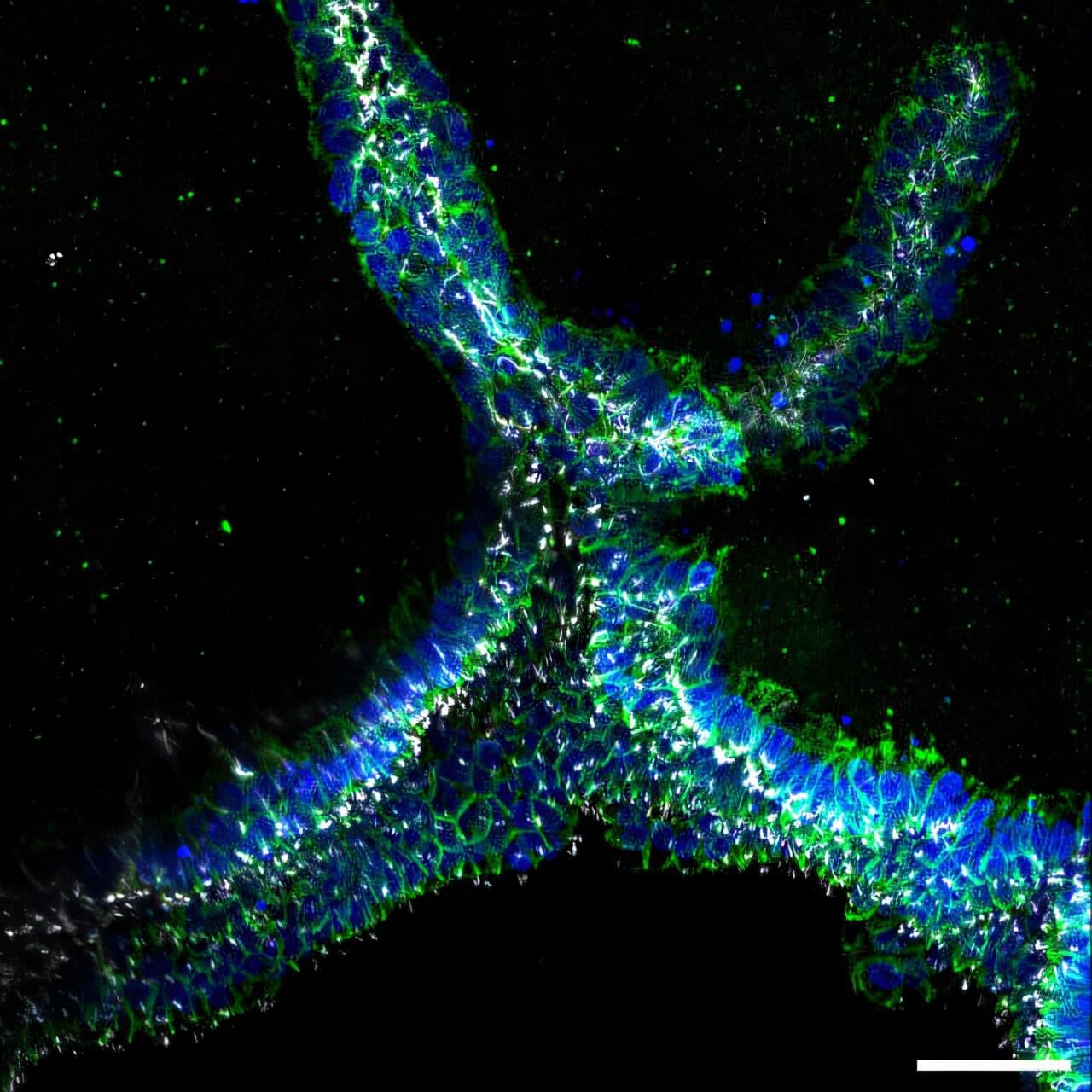

The human kidney filters about a cup of blood every minute, removing waste, excess fluid, and toxins from it, while also regulating blood pressure, balancing important electrolytes, activating Vitamin D, and helping the body produce red blood cells. This broad range of functions is achieved in part via the kidney’s complex organization. In its outer region, more than a million microscopic units, known as nephrons, filter blood, reabsorb necessary nutrients, and secrete waste in the form of urine.

To direct urine produced by this enormous number of blood-filtering units to a single ureter, the kidney establishes a highly branched three-dimensional, tree-like system of “collecting ducts” during its development. In addition to directing urine flow to the ureter and ultimately out of the kidney, collecting ducts reabsorb water that the body needs to retain, and maintain, the body’s balance of salts and acidity at healthy levels.

Finding ways to recreate this system of collecting ducts is the focus of researchers and bioengineers who are interested in understanding how duct defects cause certain kidney diseases, underdeveloped kidneys, or even the complete absence of a kidney. Being able to fabricate the kidney’s plumbing system from the bottom up would be a giant step toward tissue replacement therapies for many patients waiting for a kidney donation: In the U.S. alone, 90,000 patients are on the kidney transplant waiting list. However, rebuilding this highly branched fluid-transporting ductal system is a formidable challenge and not possible yet.